So I’ve dropped all semblance of an attempt to wrest control of the direction of this story and am going with the flow.

It was the end of February of 1987 when we finished shooting the second half of How To Be Louise. To my eye, the dailies were stunning. The performances by Lea Floden and Bruce McCarty were beyond my wildest dreams. The performances by the circle of friends they’d cast in the other roles were equally top-notch, friends like theatrical legends Maggie Burke and Lisa Emery, Mary Carol Johnson, Hollywood and tv regular Josh Pais, and Michael Patrick King (who went on to write, produce and direct Sex and the City, The Comeback and more).

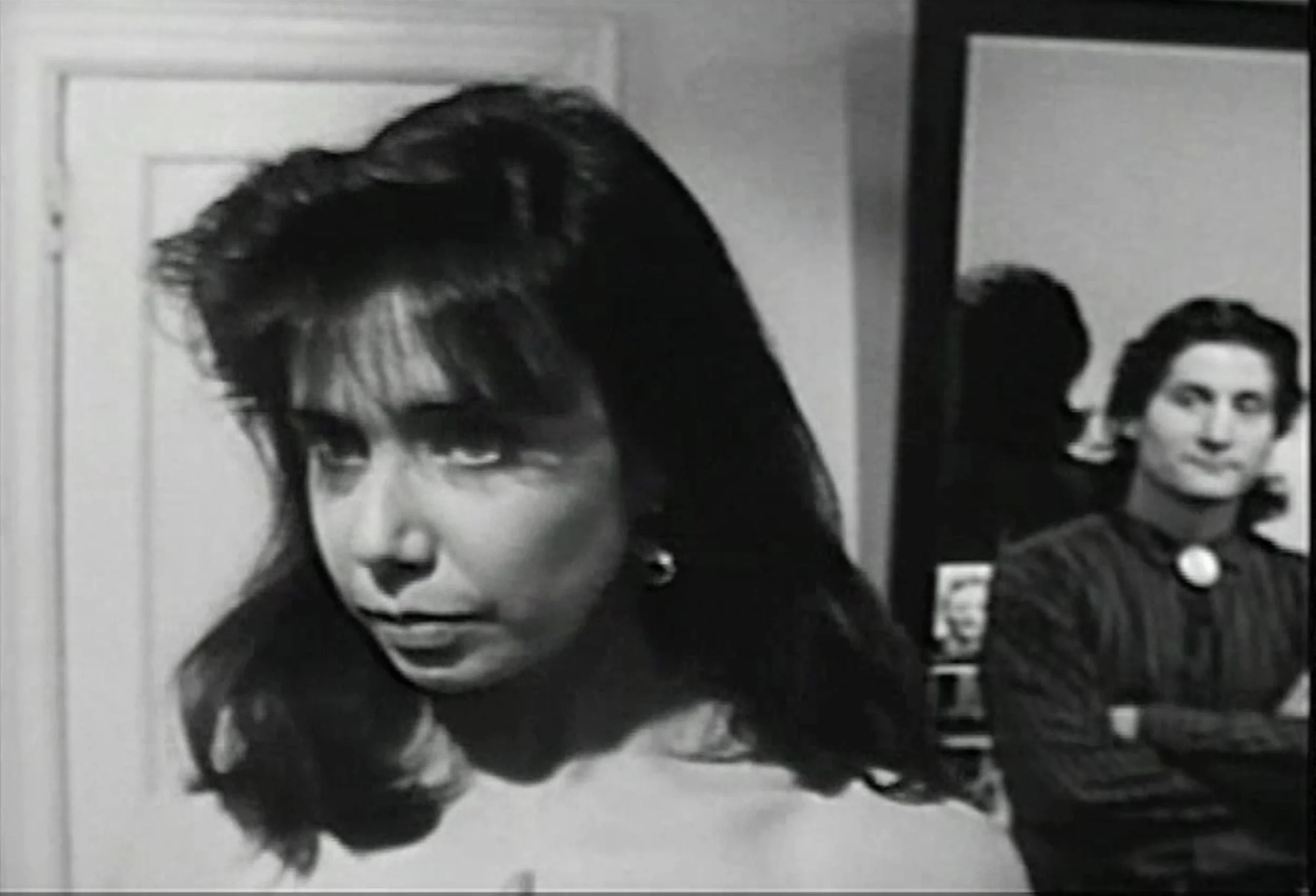

Lea Floden and Bruce McCarty in the scene about which The New York Post said: "This is very sexy."

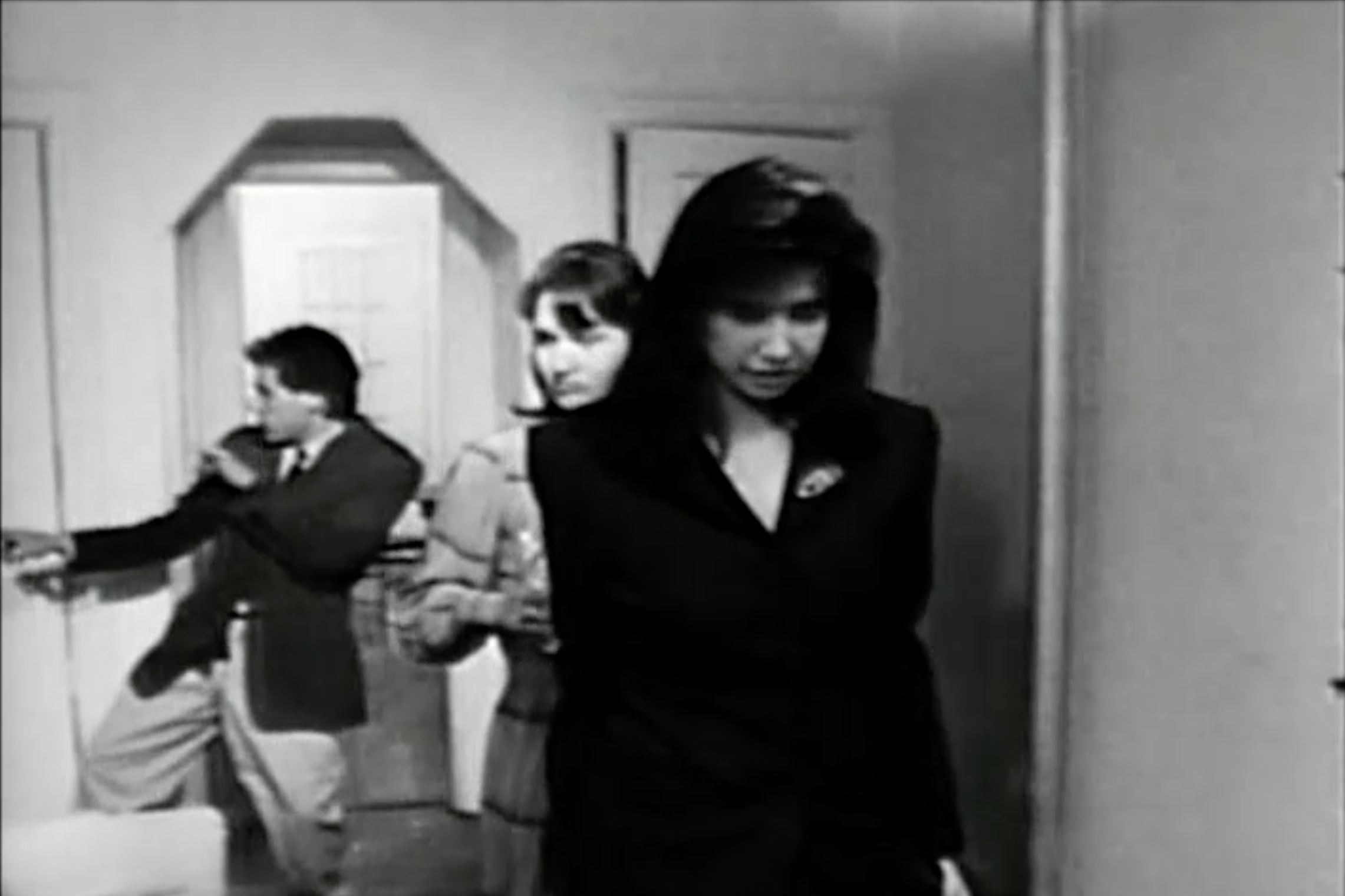

Lisa Emery, Josh Pais and Steve Simpson

Josh Pais (dancing with himself in the mirror), Mary Carol Johnson and Lea Floden

Michael Patrick King and Alice Spivak on the steps of the WIlliamsburgh Savings Bank on Broadway near Peter Luger's

Maggie Burke

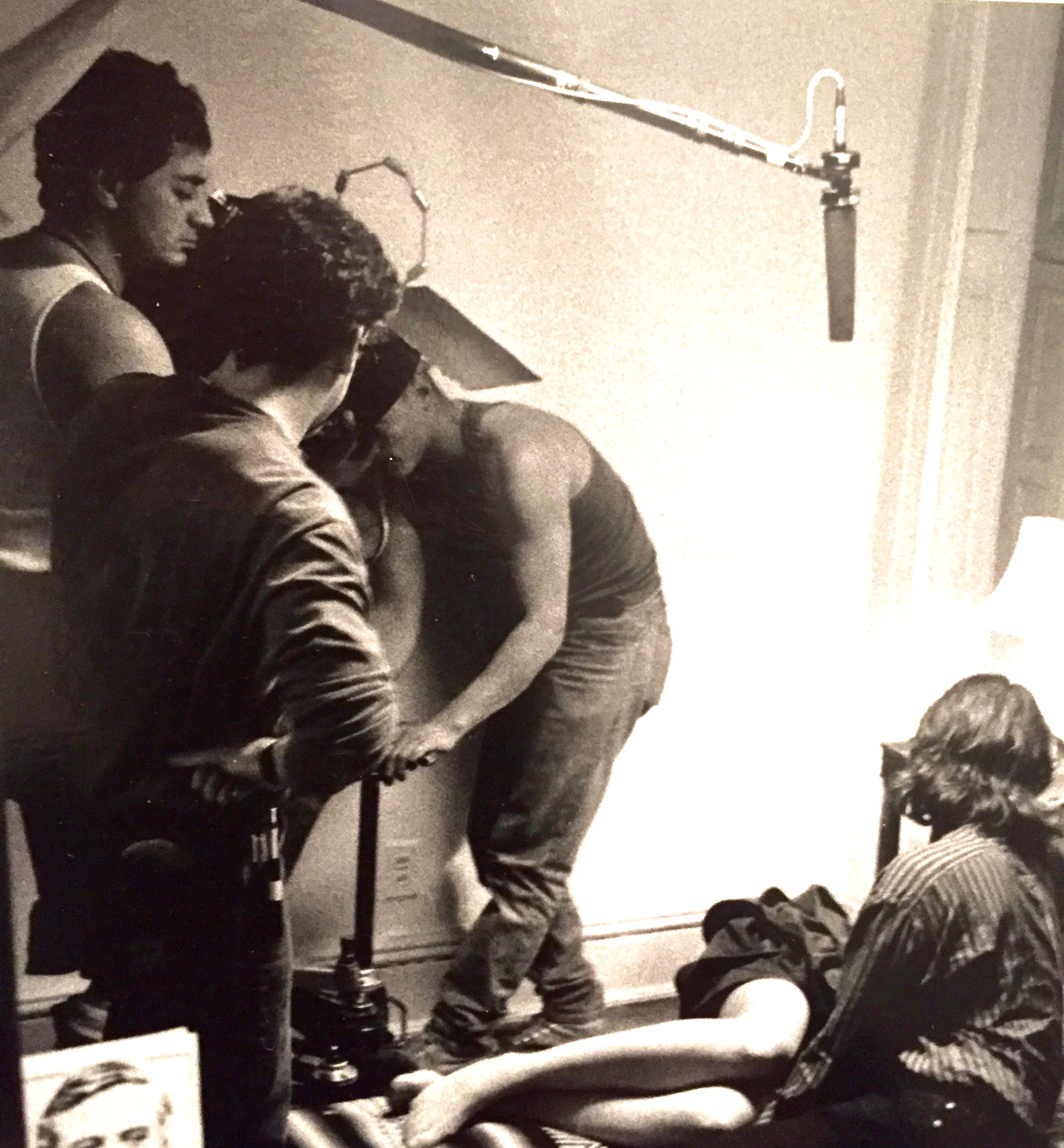

Our Director of Photography Vladimir Tukan had shot footage which itself had a power and beauty independent of the story. Yes it was 16mm, but it was luminously rich black and white: Vladimir had studied cinematography in the classic old school tradition in Russia. He was passionately committed to this film, so much so that there were more than a few unforgettable moments when I had to put my foot down about the complexity of the camera moves. In pre-production, we’d watched Bunuel’s Viridiana and The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz specifically for the long moving shots. Vladimir was going to the mat to give me what I wanted, so much so that I once had to pull out all the stops and use tears to get him to agree to a simpler shot.

Along with the job he did shooting HTBL and Nadja Yet, I'll always be grateful to Vladimir for a life lesson he taught me as one artist to another. Sometimes, in the heat of the moment of blocking and framing a shot, I'd lose my confidence and dismiss what I'd sketched out in a storyboard. Vladimir would turn to me with the full force of his considerable personality: "No! Ehnn!" (That's a phonetic spelling of my name with Vladimir's accent.) "Don't deesmiss your idea. That comes from unconscious. That's very valuable. Let's see if we can do it."

Vladimir is on the left in profile.

And we did. And when we finished, it looked so good. I realized that we weren’t just going to be able to have a babysitter, we’d be on Fifth Avenue with a nanny. I got pregnant within the month.

While Walis Johnson assembled a rough cut, I wrote every person and grant organization I could get to, asking for money for post-production.

Flash-forward three months: the production had run aground, out of money. I painted the apartment and sewed curtains for every window in it. Our downstairs neighbor Charles came up and commented to Mr. Green that I’d turned the place into a womb.

One day, getting thick around the middle and out of breath trying to do a little yoga stretch, the full reality hit me: I’ve really done it this time, seriously shot myself in the foot. I was exhausted and couldn’t even touch my toes. How was I ever going to finish this film? A voice in my head I didn’t know answered: “You’re on the right track.”

And so I went back to taking the tiny little actions I could. We got a very nice grant from The Jerome Foundation. Amy Taubin wrote a profile piece for the Village Voice which a young man in Rockford, Illinois read and then sent us $5000. And we got other donations including a big one from someone who seemed so cheap that I’d thought twice about wasting a postage stamp on him.

We screened at what was then called the Independent Feature Project (IFP) in New York in October. Ulrich Gregor of the Forum at the Berlin Film Festival ran at me after the screening: “Are you the filmmaker? I LOVE this film!” A well-connected entertainment lawyer from Los Angeles told me to call him. Jim Stark who had produced my favorite indie film Stranger Than Paradise stopped in to one of the screenings and gave a thumbs up: “You’ve got something there.” This was happening.

The sardonic and sometimes dark Philip Johnston started composing a score with his band The Happy New Yorkers and Kathleen Killeen worked on locking the picture.

Ten weeks later, Frank Thurston Green was born. Someone told me about a documentary filmmaker who gave birth to her first child on Sunday and went back to work on Monday. The story made me wonder about both my commitment to film and her sanity. My picture wasn’t locked, the sound was still to be edited, the score had to be recorded and laid in and I didn’t give a damn about any of it. I was out of my mind with hormones and sleeplessness and falling madly in love with this chubby little baby.

The next thing I remember was feeling irritated that my attempt to lay in the music (as if it were wall-to-wall carpet) had ruined the film. Fortunately Mr. Green has a deep intuitive connection to storytelling and somehow knew how to cut in the score so it would amplify instead of flattening out the story.

Soon after, we scheduled a sound mix with Dominick Tavella at Sound One. As an assistant film editor, I’d been to many sound mixes, dreaming of the day when I’d be the director working with the mixer. But as my passion for this baby was growing, so was my irritation at any distraction that could take me away from him. Self-discipline pure and simple got me on the M train to the F train to midtown and the mix. And then there was what I thought was ‘the last step’ of my job: submitting to film festivals. Sundance and Berlin were at the top of our list.

In the meantime, Mr. Green had been invited to spend six months as a guest professor at Osaka University in Japan. Of course we would go with him. But what if the film got into festivals? Mr. Green and I agreed that we’d “work it out.”

Ulrich Gregor from Berlin’s Forum, who had professed love for our rough cut the year before, was the first to respond. In a dagger to my heart, he let us know (by telegram, I think) that he wasn’t excited about the final film and had passed on it. I was packing suitcases and chasing Frank, now an energetic nine-month old, as he crawled around the apartment terrorizing the cat. Still there was no word from Sundance. This was 1989, before email and cell phones and I was frantic that, off in a suburb of Osaka, I might never get word from Sundance or any of the other festivals we'd submitted to.

The night before we left for Japan, I got the phone call from Sundance that they wanted How To Be Louise for the Dramatic Competition. Soon after, Manfred Salzgeber, curator of the Berlin Festival’s Panorama, sent similarly good news.

(to be continued)

Click the 'Like' button below for some serious immediate gratification. Not kidding.